75

Honour Lectures /

Conférences honorifiques

Proceedings of the 18

th

International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering, Paris 2013

A detailed history of the tower and the nearby Cathedral

(Labate 2009), their original design and subsequent

modifications, was obtained from the study of many archive

documents and was checked against the comparison of the

material and stylistic characteristics of the various masonry

levels of both buildings. In addition, on the basis of

archeological escavations made in 1913 (Sandonnini, 1983) and

more recent investigations (Labate, 2009), it was possible to

identify the position of the late medieval cathedral, the pre-

Lanfranco cathedral and the actual Lanfranco cathedral (Fig. 8).

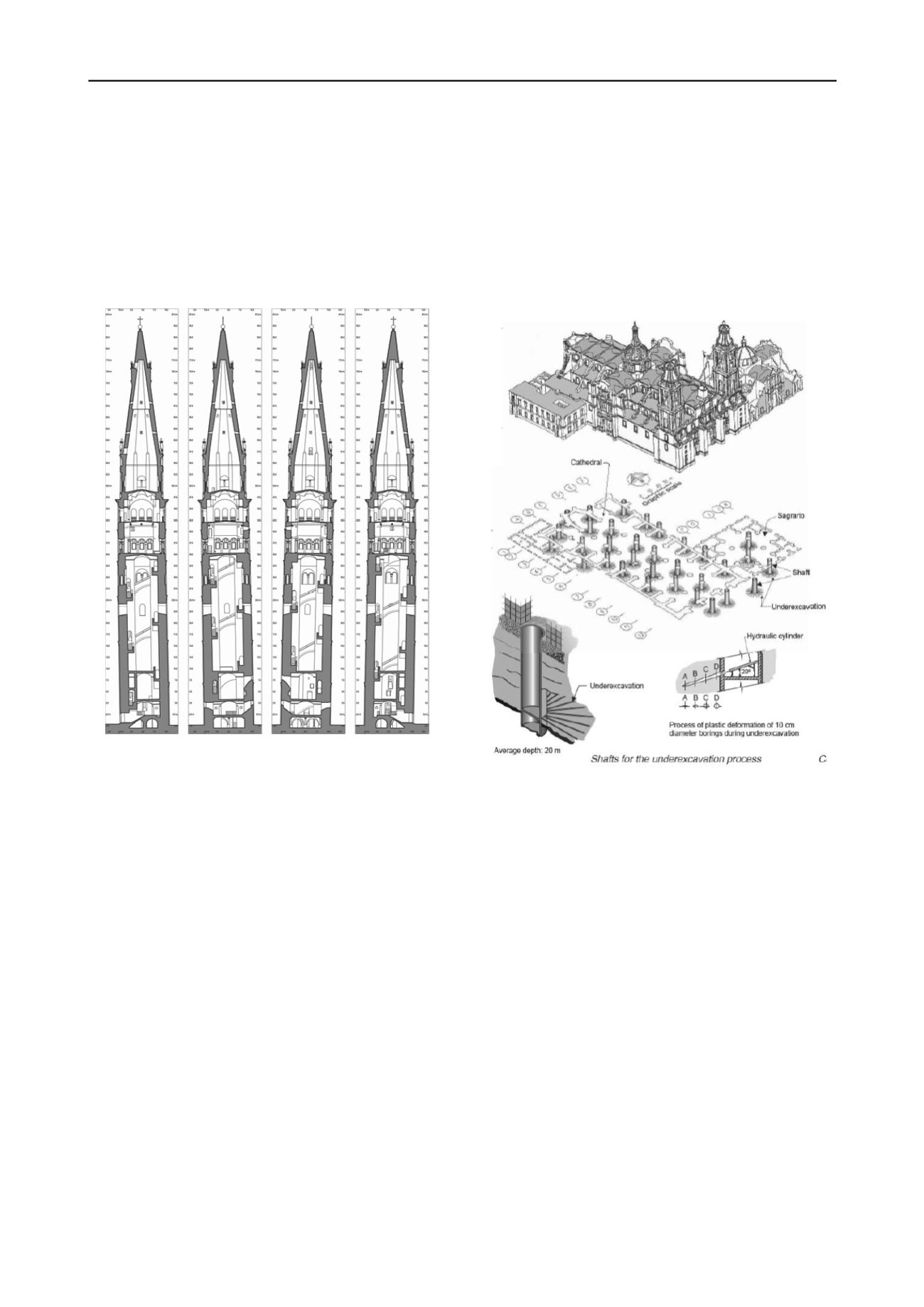

Figure 9. Vertical sections of Ghirlandina tower: from the left, view

towards West, view towards North, view towards South, view towards

East (Lancellotta 2013).

Since the foundation soil has “memory” of the previous

loading history, this detailed reconstruction was the key to

explain the differential settlements, suffered by the cathedral

and in particular the tilt of its apse towards East and not only

towards the Ghirlandina tower.

Additional borings allowed to identify a detailed profile of

the soil upper layer and to find the remains of the ancient

Roman road Via Aemilia at a depth of about 7 m. By comparing

the different elevations of its pavement below the tower and

outside, it became possible to deduce the settlements of the

tower and the compressibility of its foundation soil. In order to

explore the stability equilibrium of the leaning tower (Cheney et

al. 1991, Di Tommaso et al. 2012) the inverted pendulum model

has been adopted. Its parameters were derived from the soil

investigations and from an experimental identification analysis

of the tower dynamic behaviour in the presence of ambient

vibration. The model parameters were chosen according to the

time histories of the tower vibration, collected by means of a set

of accelerometers at different heights; then a thorough analysis

of soil-structure interaction was carried out in order to get a

reliable estimate of the rotational stiffness and of the dynamic

response of the tower foundation. The results gave reason for

the good performance of the tower during the past seismic

events and showed that there is no need for underpinning

interventions. Furthermore it appeared that if the tower had been

underpinned on micropiles, following the dogmatic trend of 20-

30 years ago, the decrease of the fundamental period of the

structure would have increased its seismic vulnerability.

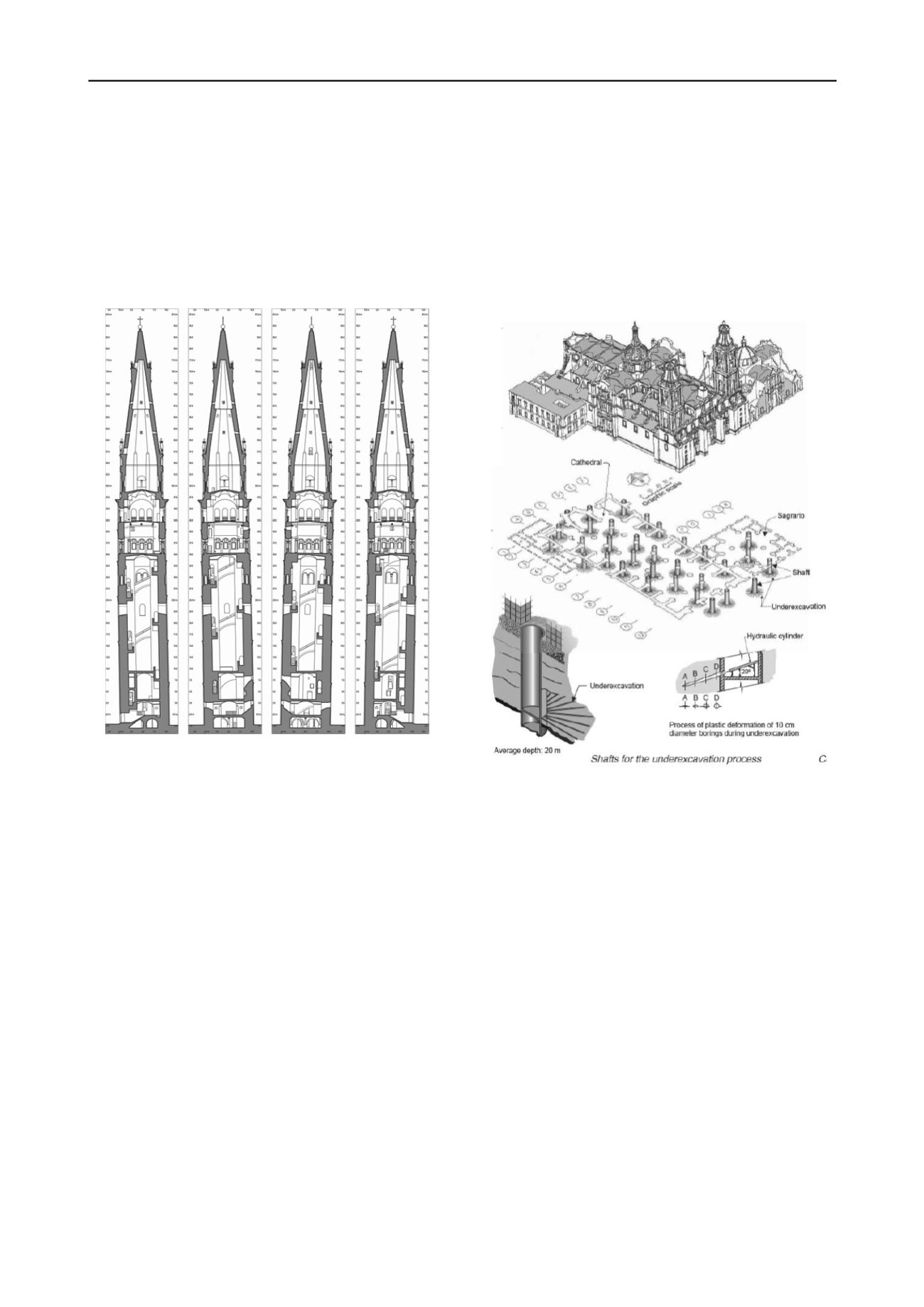

In this connection another emblematic and famous case is

the Cathedral of Mexico City (Ovando-Shelley et al. 1997,

Tamez et al. 1997, Santoyo and Ovando-Shelley 2000, Ovando-

Shelley and Santoyo 2001). Historic information made it

possible to identify the origin of the differential settlements of

the foundation soil, part of which had been consolidated by pre-

Columbian works, and to design sub-excavation and soil

consolidation measures to offset the differential settlements

(Fig. 10). On the other hand, the studies on foundations have

contributed to a thorough understanding of the historic events of

the Cathedral and of the surrounding area.

Figure 10. Underexcavation at the Cathedral of Mexico City (Santoyo

and Ovando-Shelley, 2000).

5 CRITICAL CASES

There is a long list of monumental buildings that, owing to the

slow or very slow displacements in the foundation planes, suffer

progressive instability. In these cases a conflict sets in between

the purely technological approach (aimed at reinstating the

safety of the monument with structural interventions which,

while ensuring that the external aspects are preserved, modify

the original structural design), and a softer approach, on the

other hand, that begins with a study of the phenomena

underlying the instability and makes a long and perhaps

uneventful search of the causes that need to be removed to stop

the instability and if possible save the monument without

substantial alterations so as to respect its historic integrity. It is

worth recalling that the search for the causes is always a time-

consuming exercise that is often much more expensive than

ordinary, obvious structural and geotechnical engineering

interventions. A systematic study of the saving projects carried

out in Italy until 1995, including buildings of different kinds

(Table 1), has shown that pure underpinning by micropiles was

the largely predominant type of measure (Fig. 11) which in

many cases was probably unnecessary or unsuited.