73

Honour Lectures /

Conférences honorifiques

Proceedings of the 18

th

International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering, Paris 2013

measures are most urgent, but it is extremely difficult and

problematic to decide on how to go about such measures.

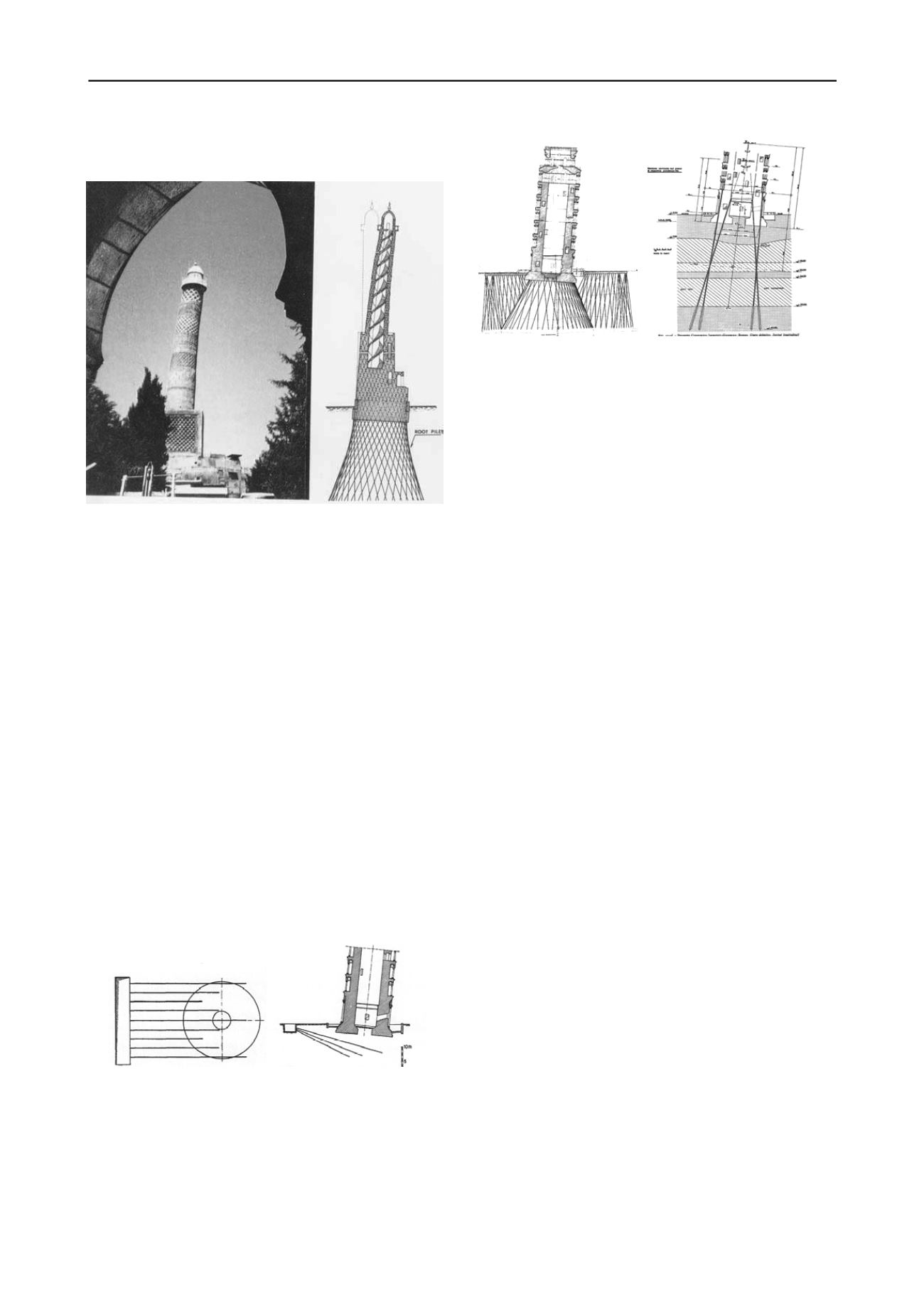

Figure 3. The Minaret of Mosul, underpinned micropiles and

structurally strengthened in 1981 (Lizzi 1982, 1997).

The role of Geotechnical Engineers in the conservation of

historic towns and monuments could be much broader and

multifaceted and even more attractive in cultural terms than

what is generally believed. The general perception of

geotechnical engineering only as a means for intervening in a

historic structure from the static standpoint is restrictive and far

from the present view of thinking about monument

conservation. Indeed it is now common thinking that the

replacement or substantial modification of a structure or of a

foundation alters or even eliminates forever an historically

essential feature of a monument, the idea being that even its non

visible parts, like the foundations, must also be preserved as a

material token of its history.

A self evident example of the changing of mind that

occurred in the course of a few decades is provided by the

Leaning Tower of Pisa: for a long time, faced with the objective

difficulty in interpreting the phenomena that were causing the

progressive inclination of the Tower, technological solutions

were offered that were intended to make the Tower independent

of the behaviour of its foundation soil. In 1962, F. Terracina, a

geotechnical engineer who was a passionate scholar of the

Tower, published a proposal (Fig. 4) that simply envisaged the

removal of soil from the uphill section (anticipating the solution

adopted 40 years later) (Terracina 1962), but its suggestion

remained unattended.

Figure 4. Layout of the underexcavation proposed by Terracina (1962).

Geotechnical Engineering had made great progress (with the

development of micropiles and consolidation techniques) and

the call for projects launched to save the Tower in 1973, after

the completion of the studies on its subsoil (Cestelli Guidi et al.

1971) attracted only projects that aimed at creating a deep-

seated underpinning (Fig. 5), across soils that were more or less

deformable (Burland et al. 2013).

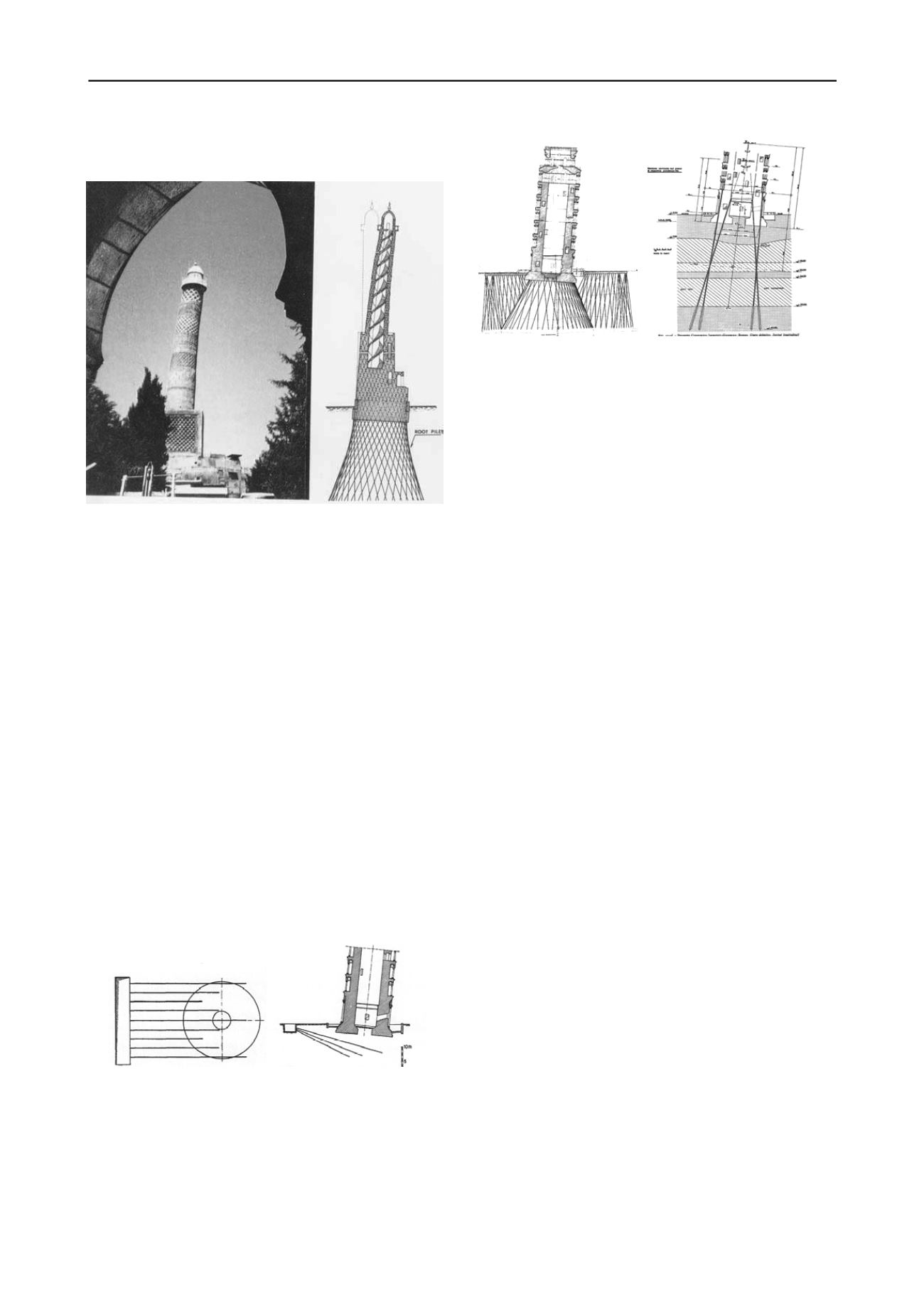

a)

b)

Figure 5. Some of the intervention measures proposed to save the Tower

of Pisa at the 1973 call for projects (Burland et al. 2013): a) Fondedile

proposal; b) Impredit-Gambogi-Rodio proposal.

Actually until the early 1990s, the concept that the

conservation of a monument involves also saving its

construction components, even those that are not visible had not

yet gained ground; the idea that the Tower of Pisa, once it were

to be transferred onto a new foundation built using the

technologies of the 20th century, would become a fake, only a

pure icon of the monument, was not understood (Calabresi and

Cestelli Guidi 1990, Calabresi 2011). The new way of thinking

made its way gradually and radically changed the cultural

approach to the consolidation of ancient buildings, and in the

case of the Tower of Pisa, it led to the solution that was finally

and happily adopted for its stabilization (Burland et al. 2000).

4 THE NEED OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY STUDIES

If the protection of a historic and monumental building has the

aim of maintaining and spreading the knowledge of past eras

and civilizations, then the study of the interaction between

buildings and the environment, and in particular their

foundation soils, brings a substantial contribution to it; it may

help understand the choices made by the designers at the time of

construction, the changes that occurred over the years, the

causes of damages, and the techniques and materials used and

relate them to the natural and artificial materials available, to

the machines and to the historic context. All this helps deepen

our knowledge of remote times. In this setting the contribution

offered by Geotechnics, alongside that offered by structural

engineers, geologists, seismologists, architects, art historians

and construction historians may play an extremely important

role. The examples of activities carried out with this spirit are

now a great many and have been quite successful with at times

unexpected and surprising results. More than thirty years ago

the archaeologist Gullini had already presented a fascinating

picture of the results achieved through cooperation between

geotechnical engineers, archaeologists and historians in

studying the developments in construction techniques and

design in antiquity (Gullini 1980). They studied the foundations

of ancient monuments and archaeological settlements in

Mesopotamia and in the Mediterranean area from the 4

th

millennium B.C. to the late Roman Empire. Today there are

many conservation projects sponsored by UNESCO which have

a multidisciplinary approach in which Geology and Geotechnics

play an essential role: for instance mention can be made of the

set of measures proposed for Greece presented by IAEG

(Christaras 2003).

An Italian example is the Valley of the Temples in

Agrigento (Croce et al. 1980.): studies carried out on the slope

stability of the area where the temples rise have contributed to a

better understanding of the history of Magna Greece and of the

technical culture of its inhabitants between the 6th and 5th

centuries B.C. within the frame of our knowledge of ancient

Greece architecture (Dinsmoor 1975).